A collaborative multimedia series with reporter Sara Schilling documenting 24 hours in the Tri-City area, spending each hour of the day with a different person. What will their hours tell us - about who they are, about who we are?

Twenty-four hours.

They can pass in the blink of an eye, or ever so slowly.

They can be filled with mundane tasks, with ordinary things. Or with big and significant moments.

Or a little of both.

Either way, they’re important.

They count.

Twenty-four hours.

A day.

Today.

It’s all the time we ever have, so it matters how we spend it.

12 A.M. For Zade Hakki, 19, his job is about more than making coffee. A lot more. A 'broista' on the graveyard shift at Dutch Bros. Coffee in Kennewick for him the job is the conversations he has with customers. He remembers one night over the holidays he spent 45 minutes in the cold windowsill talking to a man who drove up at 2 a.m. He doesn't remember what the conversation was about but he remembers what the man said when he drove away, 'Hey' he said 'I was going to kill myself tonight. Thank you so much for talking to me and making me feel like someone cares about me.'

"I just thought I was making a cup of coffee for a dude, just talking," Hakki recounts, shaking. "It's crazy what that can do."

1 A.M. It was a little after 1 a.m. in the emergency department at Trios Southridge Hospital and all the patients -there were only three at the moment- were taken care of. But overnight charge nurse Patsy Haeg, 61, still had plenty to do. "They call me den mother around here," said Haeg. And she is, not just of her son's cub scout group but of her family, her coworkers and her patients.

2 A.M. In the perpetual adoration chapel at St. Joseph Catholic Church you can almost hear the candles flicker. That is exactly how Carol LeCompte, 66 of Kenenwick, likes her second home. LeCompte, who helped organize the program in 1997, now manages the 200 volunteers who take turns praying and worshipping God in the chapel around the clock. She frequently volunteers for overnight shifts, subbing when others are absent.

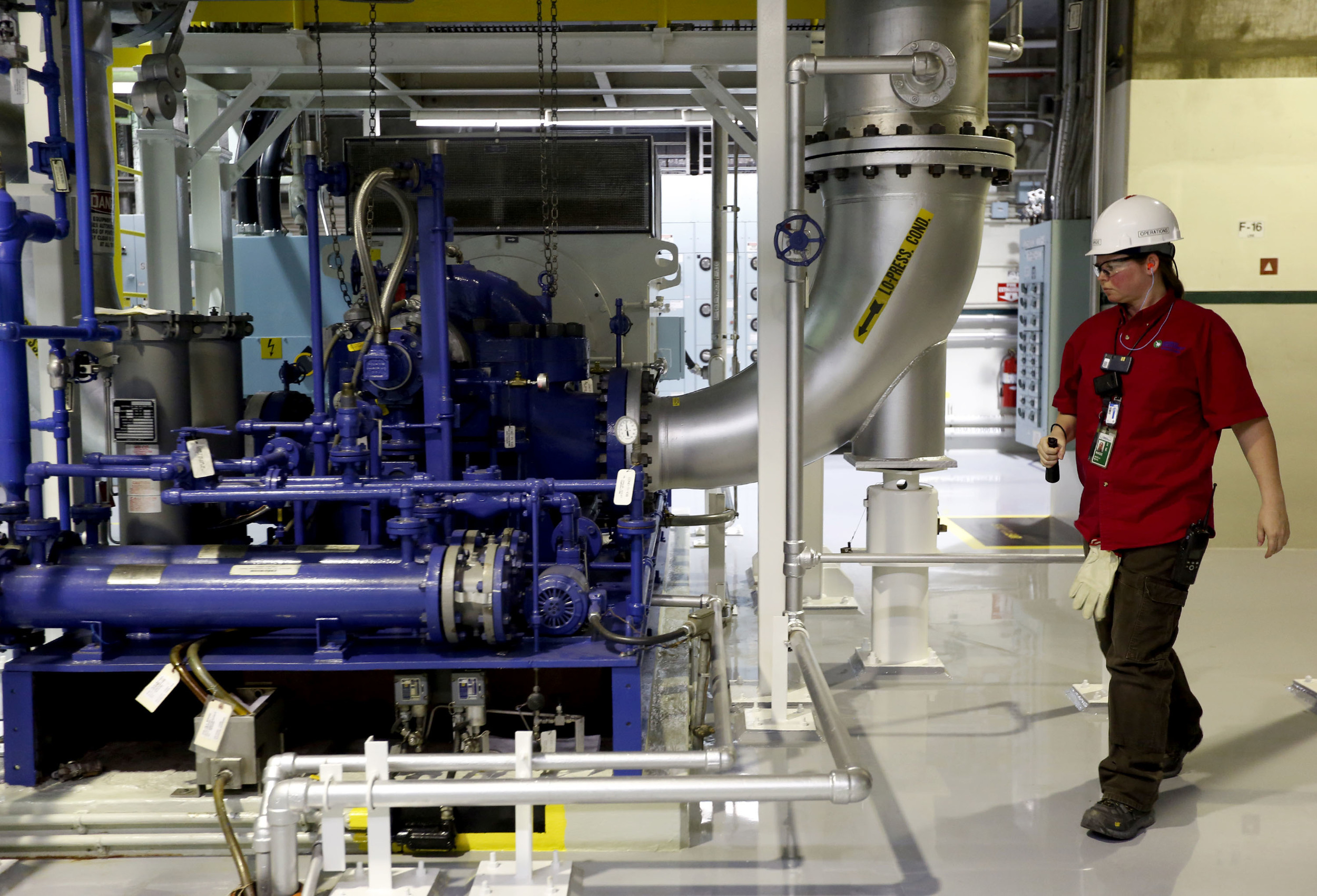

3 A.M. Angela Deahl isn't a coffee drinker. Her six years in the Navy didn't her her hooked on the stuff and neither did years of shift work as an equipment operator at the Columbia Generating Station. Deahl knows her way through the complicated maze of machinery, long hallways and heavy doors. It all makes sense to her, one of two women on a team of 39 at the only commercial nuclear power plant in the region. "I don't even think about it," she said of being the only woman. "I just do my job."

4 A.M. Mary Wister fell in love with weather as a kid. She'd watch the weather reports at night with her father, pore over old weather maps used by pilots and measure hail with a cartoon ruler wearing her brothers football helmet for protection. Now the 45 year-old meteorologist has returned to the forecast desk at National Weather Service in Pendleton after a few years in management. "I'd sit in my office and long to be out in the open room surrounded by the maps trying to understand this complicated thing we call weather," she said of her time as the boss.

5 A.M. Steven Whitehead speaks with a Louisiana slow drawl not often heard in the northwest. A place he never expected to stay for long. When he was recruited to play for the Tri-Cities Fever he saw it as a quick step in his football career. As he got involved in the community he saw a need for youth sports training and grew his passion of working with young athletes. Through Elite Ambitions Whitehead and his team offer sports performance training for kids from elementary through high school, even offering a scholarship program. A group of high school football players listen intently to him during a weight training session before school at 5:30 a.m. "We're like the mechanics, helping to tune up the young athletes," Whitehead said. Somewhere along the way many of his kids also find their way to becoming better students, better people.